Repairs have been made and full system tests were performed successfully last night. I still have one cosmetic fix to complete, but the PTO is back online.

I’m standing down the observatory for some much needed maintenance. Hopefully, it should only be 3-4 days.

The PTO has one camera dedicated to meteor search. The All-Sky camera that feeds the PTO web site Sky Conditions page and the Weather Underground can also detect meteors if they are bright enough. The problems with both of those are the tree line at the PTO and the bright local sky. I wanted a meteor camera that I can take to dark sky locations. So, I cobbled together a spare camera and a lens. I was finally able to test the system on the 12th of August. Several members of the NWFAA met at a dark site near Munson, FL to observe the Perseid meteor shower peak on Saturday evening.

The system consists of a video camera that feeds a GPS time inserter so each video frame can be time stamped. The output video stream is fed to an analog-to-USB converter dongle which then feeds a laptop running meteor detection software. In my case, the software is HandyAvi. The camera is a WATEC WAT-902H2 Ultimate and has a Fujinon 1.4mm fisheye lens on it.

|

|

I arrived at the observing site well before sunset so I could set everything up in daylight. The picture supplied by the system was very sharp and bright. But the darker the skies got, the more the picture deteriorated and by the time the sky was fully dark, the picture was so noisy as to be unusable. I tried rerouting power and signal cables and restarted the camera to no avail. So, I shut everything down, packed up and reverted to visual observation. Unfortunately, the cloud cover prevented viewing all but a couple of meteors and eventually we all gave up.

Once home I re-assembled the system in the back yard for some additional testing. I was able to reduce the noise by switching to a manual gain control mode, but even then the camera did not show anything but Vega and a local street light. The camera does not have an integrating mode so it is not as sensitive as I would like.

I regrouped and switched to a different camera. This one is a Imaging Source DMK-21AU618 USB camera and is capable of integrating its output. I don’t currently have a way to insert a time stamp. However, even if the software can detect a meteor, there is no way to know when in the integration time period the meteor struck, so a very accurate time code is not useful.

So, back into the back yard. During the test, the PTO was running an asteroid observing plan. Notice the dome tracking the night sky. There are flashes from local traffic and what appears to be one short satellite trail. Just by looking at the star patterns, the limiting magnitude is right about 6.0. Not only are the star clouds of the Milky Way visible, about 5 seconds into the video, the Andromeda Galaxy comes into view. It is only a small fuzzy smudge, but it is visible. Just before the video ends some glare from the rising Moon starts to intrude. The video is a animation assembled from 282 twenty second exposures.

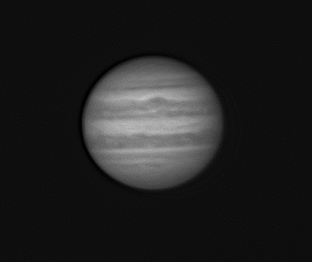

The sky last night was one of the darkest (and clearest) we have had in quite a few weeks. I was able to get a short JunoCam series before Jupiter hit my western tree line.

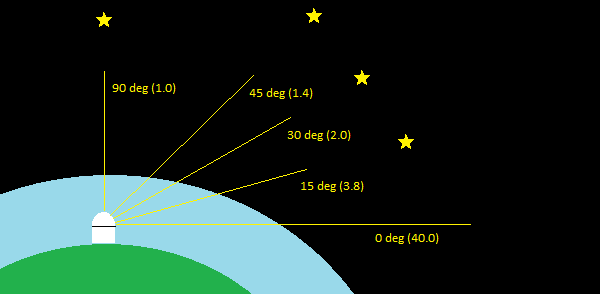

Ideally, if you want to image for an hour, the best time as far as the atmosphere is concerned, is the half-hour before the target gets to the zenith and the half-hour after it passes the zenith. But right now Jupiter gets only 55° high and is well past the meridian before the sky gets dark. That means the planet starts with less than optimal airmass and as the night progresses descends into ever increasing airmass.

Airmass is the length of the pathway through the atmosphere that the photons from the object you are looking at have to pass. The path length above the zenith is about 100 km and the path length along the horizon is about 1020 km. By definition, airmass is 1.0 for an object directly on the observer’s zenith. The lower in the sky, the higher the airmass gets. The longer atmospheric path means more distortion, absorption and refraction.

Close to the horizon, the object doesn’t look like it really does (distortion), isn’t as bright as it really is (absorption) and isn’t where it looks like it is (refraction).

Last night the SkySentinel meteor camera that I host here at the PTO caught sight of a set of sprites as a weather front approached from the northwest. Sprites are only one of several “Transient Luminous Events” associated with thunderstorms. Reports by pilots of ‘lightning’ above the clouds were once dismissed outright by meteorologists. Once directly imaged in 1989 and finally accepted by scientists as a real phenomenon, sprites and their relations have been recorded all over the planet as well as from the International Space Station. One estimate has several million of these high-altitude events occur each year.

These electrical discharges occur 50-90 kilometers above the ground. The sprites in this video are only visible on two frames. Look carefully and you will see the flash of ‘normal’ lightning reflecting off of low lying clouds immediately after the sprites.